As of the end of July, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage stands at 5.3% compared to just 3.2% at the start of the year and about 2.8% a year ago. The rapid rise in mortgage rates in 2022, following historically low levels since the onset of the pandemic, has raised questions about the Federal Reserve’s influence as well as the relationship between the federal funds rate and mortgage rates.

At the most recent Federal Open Market Committee meeting, the Federal Reserve continued its aggressive tightening policy stance in response to rising inflation which is running at a 40-year high. As expected, officials lifted the benchmark federal funds rate by 75 basis points for the second consecutive month— marking the steepest 2 month rise since the early 1980s—moving its target range to between 2.25% and 2.5%. While the dynamics of monetary policy, capital markets, and various consumer interest rates are complex and the intricacies are beyond the scope of this report, this primer provides a brief, high-level overview of how and to what degree the Federal Reserve affects fixed-rate mortgages.

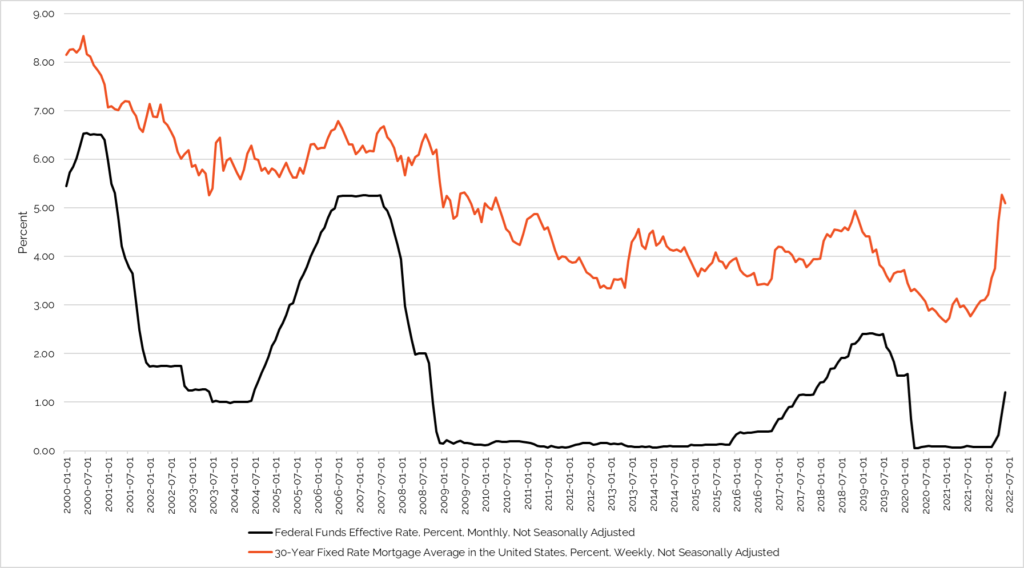

The federal funds rate—the interest rate that banks charge one another to lend funds overnight—is one of the most important tools in the Fed’s arsenal. It sets the floor for all other interest rates on private and government debt. It is a common misconception that the Fed directly influences mortgage rates. A look at the historical movement between the two shows that the correlation is quite weak. For example, between 2004 and 2006 the federal funds rate was steadily increased from 1% to more than 5%, while during the same span mortgage rates remained steady at approximately 6%. As shown below, the spread between the federal funds rate and fixed-rate mortgages over the past 20 years has varied between 1% and 5%.

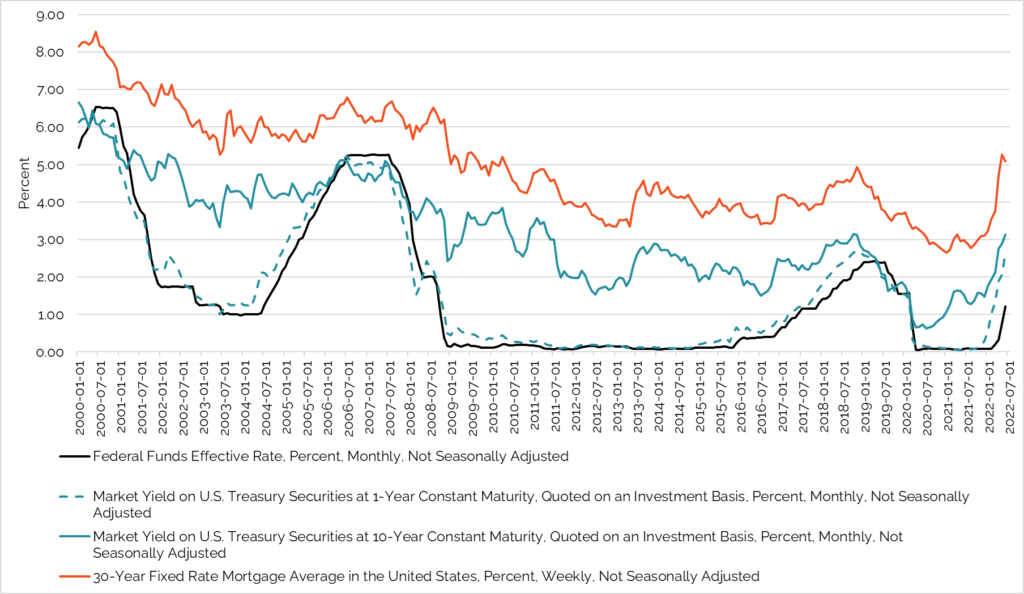

Mortgage rates are instead much more correlated to 10-Year Treasury yields. When it comes to financial products, US Treasury fixed-income securities (bills, notes, and bonds) are the safest investment because the US government guarantees them. To attract investors, any product riskier than a Treasury with the same maturity must offer a higher yield to account for risk. The following graph charts the historic movement of the federal funds rate with both short and long-term Treasuries as well as the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage.

Historical data indicates that the federal funds rate and yields on short-term securities, such as the 1-year Treasury, move in tandem. In contrast, the federal funds rate and 10-year Treasuries display a degree of co-movement though they are not in lockstep. This is because long-term security yields reflect market expectations of future interest rate fluctuations such that by the time the Fed changes its benchmark target, the decision has already been priced in.

Mortgage rates tie into this analysis as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) are a competing financial product with long-term Treasuries. A mortgage-backed security is, in its simplest form, an asset secured by a mortgage or a collection of mortgages. While 10-year Treasuries are backed by the “full faith and credit” of the U.S. government, MBS are subject to a high degree of risk as mortgages are susceptible to default, offer lower liquidity, and a longer term. To attract investors, MBS must offer a higher yield than Treasury bonds such that when Treasury yields increase, lenders must raise interest rates on the mortgages inside MBS to compete. Traditionally, the spread between the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage and 10-year Treasury has been around 2%.

A historical look at the movement of the federal funds rate and 30-year fixed-rate mortgage shows that while there is some co- movement, the Federal Reserve does not directly influence fixed-rate mortgages via its benchmark interest rate. Fixed-rate mortgages are instead closely tied to the bond market, particularly 10-year Treasuries. It is important to note; however, that this primer is a simplified and high-level overview. The Federal Reserve can and has in fact influenced mortgage rates via policies such as quantitative easing and tightening which can explain much of the movement in fixed-rate mortgages following the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the scope of this paper is limited to 30-year fixed-rate mortgages; it does not touch on adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) which are more closely linked to the federal funds rate.

All information is from sources deemed reliable but no guarantee is made as to its accuracy. All material presented herein is intended for informational purposes only and is subject to human errors, omissions, changes or withdrawals without notice.